Former president Thabo Mbeki, without question South Africa’s most internationally-oriented president, gave a speech about the state of South Africa’s foreign policy in November this year. He spoke to a high-profile audience of diplomats and policymakers, and he was not kind. On an array of issues — violence in the Sahel region, ethnic tensions in Ethiopia, the civil war in South Sudan, the United States-China trade war, the rise of Europe’s far right, civil unrest in Latin America, US President Donald Trump — Mbeki accused South Africa of failing to articulate a clear and consistent foreign policy.

“What does our country think about that? What are we doing about it? I’m saying I don’t know if we’ve got any policy about matters of that kind,” he said. The audience applauded in agreement (and everyone was too polite to point out the obvious irony: that it was Mbeki himself who pioneered South Africa’s infamous policy of ‘quiet diplomacy’).

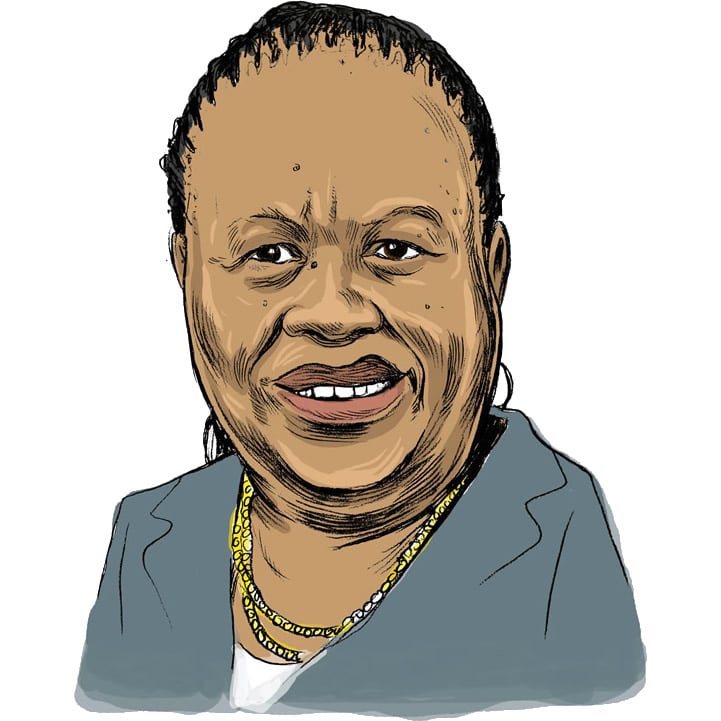

This lack of clarity is one of several challenges facing Pandor, who assumed control of the department of international relations and co-operation in May.

She inherited a ministry that has been demoralised by several major foreign policy failures, most significantly the bruising battle to install Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma as chairperson of the African Union Commission in 2012, which irreparably dented South Africa’s continental standing. Then there was the humiliating episode late last year when South Africa’s ambassador to the United Nations went rogue and voted to abstain from condemning human rights abuses in Burma. (This was later reversed by a furious Lindiwe Sisulu, Pandor’s immediate predecessor).

Having been in the job for less than a year, it is difficult to accurately gauge Pandor’s progress. It is troubling that we had to say almost the exact same thing this time last year about Sisulu, who ultimately spent only 15 months in the job. Consistent foreign policy requires consistent leadership.

But Pandor has already made her mark in some respects, despite her self-confessed lack of experience in the diplomatic arena.

“I’ve had on occasion confessed to [Zimbabwean] president Robert Mugabe that I have no diplomatic skills whatsoever. I used to tell him I’m very bad at protocol matters. I’ve promised President Cyril Ramaphosa that I am going to learn and I’m illustrating to you that this is my beginning,” she said in her first address to the department.

Department officials say she is much more hands-on than either Sisulu or Sisulu’s predecessor, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, and takes an active interest in the information presented to her. Senior officials, unused to being questioned, are having to prepare much more thoroughly for briefings. “08:30 means 08:30,” she told staff. “I believe in competence, I believe in hard work.”

Pandor has also made it known in the diplomatic community that she intends to “professionalise” ambassadorial postings, drawing more ambassadors from the department. This is presumably to avoid scandals such as the one that has enveloped the ambassador to the UN in Geneva, Nozipho Mxakato-Diseko, who has been accused of bullying staff at that embassy.

These internal reforms are yet to manifest publicly. The country’s most significant foreign policy foray this year has been its appointment as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council. But critics have said that South Africa has not clearly articulated its priorities for its two-year term, and has yet to have any real effect.

This became especially apparent in October, during South Africa’s month as security council chair. The position gives the occupant a chance to highlight their priorities, but two South African initiatives went down badly. Resistance from the US and Russia forced the watering down of a resolution on gender, peace and security, while the AU’s Peace and Security Council declined to approve the tabling of an initiative on AU funding.

Pandor faced a major challenge in the wake of the increased xenophobic violence in September, which caused tensions with other African governments, especially Nigeria. She did not pass this test with flying colours.

In a meeting with representatives of migrants in South Africa, Pandor did not apologise, and she tried to downplay the problem, criticising other African countries who failed to provide for their citizens. In separate comments, she blamed “the media” for depicting South Africa as xenophobic.

Next year, President Cyril Ramaphosa is due to chair the AU. From an international relations perspective, this could be among the defining moments of his presidency — and Pandor will play a vital role in whether South Africa is able to advance its foreign policy priorities on the continental stage. If anyone can figure out what those priorities are.